A Lake Too Far

‘In the mountains worldly attachments are left behind, and in the absence of material distractions, we are opened up to spiritual thought. We should be attempting to carry the spiritual experience of the mountains with us everywhere.’

—Jamling Tenzing Norgay

The Zanskar cycling expedition left a deep imprint on my life, opening the gates of my soul to a world that I longed to continue to explore. It deepened my spiritual beliefs and the power of grit and determination to achieve insurmountable goals. With limited experience but rigorous training, my friends and I had ascended one of the highest passes in the world on one of its most treacherous roads. The lessons of this journey reverberated in every sphere of life. It also emboldened me to set my sights on other high passes in the Himalaya and in late winter of 2012 I began my explorations for the next big adventure.

In December 2012, while searching for a worthy summit, I discovered that one of the highest lakes in India, Lake Gurudongmar, was located at an altitude of 5,425 m/17,800 ft and was not only pristine and unspoilt but one of the holiest places for Buddhists, Hindus and Sikhs alike and had been named after Guru Padmasambhava, the founder of Tibetan Buddhism. This was of particular interest to me because of my growing closeness to Buddhism and its values. I had only just begun to read the books by the Dalai Lama and Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche, and while I was familiar with some of the basic teachings, I was beginning to delve deeper towards not just the words but practising compassion and the qualities of forgiveness in my daily life. My bicycling journeys always had a deeper meaning embedded in them and as I evolved, I realized that the spiritual in me sought answers in the silence of nature and the adventure trails were intertwined inexplicably in my deeper quest and thirst for

It was on the morning of the fourth day in Gangtok, and two days behind schedule, that the three of us began our expedition to Lake Gurudongmar with Palden ahead of us in the Mahindra with the supplies and our gear. It was a chilly but sunny morning; we all had mounted on our backs a 15 L cycling backpack loaded with our day’s food rations and water hydration bags. We were headed to Mangan, 52 km away, our first halt. We climbed onto a village road away from the main highway and found ourselves on a ridge overlooking the mighty snow peaks of the Himalaya in the distance and a fantastic view of Mt Kanchenjunja or ‘Khangchendzonga’. It is the third highest mountain in the world and is believed to be the abode of the goddess Yuma. The word Kanchenjunga or ‘Senjelungma’, in the Limbu language, also means the ‘Five Treasures of the Snow’ which are salt, gold, turquoise, precious stones and sacred scriptures; hence the mountain itself is forbidden from being climbed to the very summit as it is held in reverence.

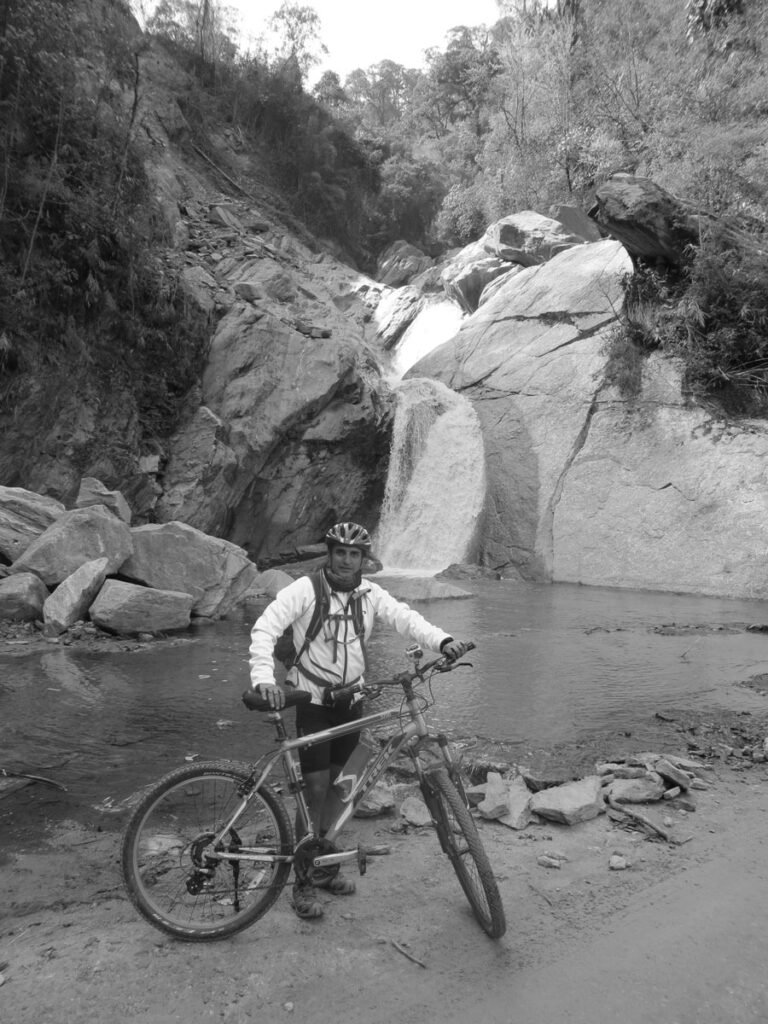

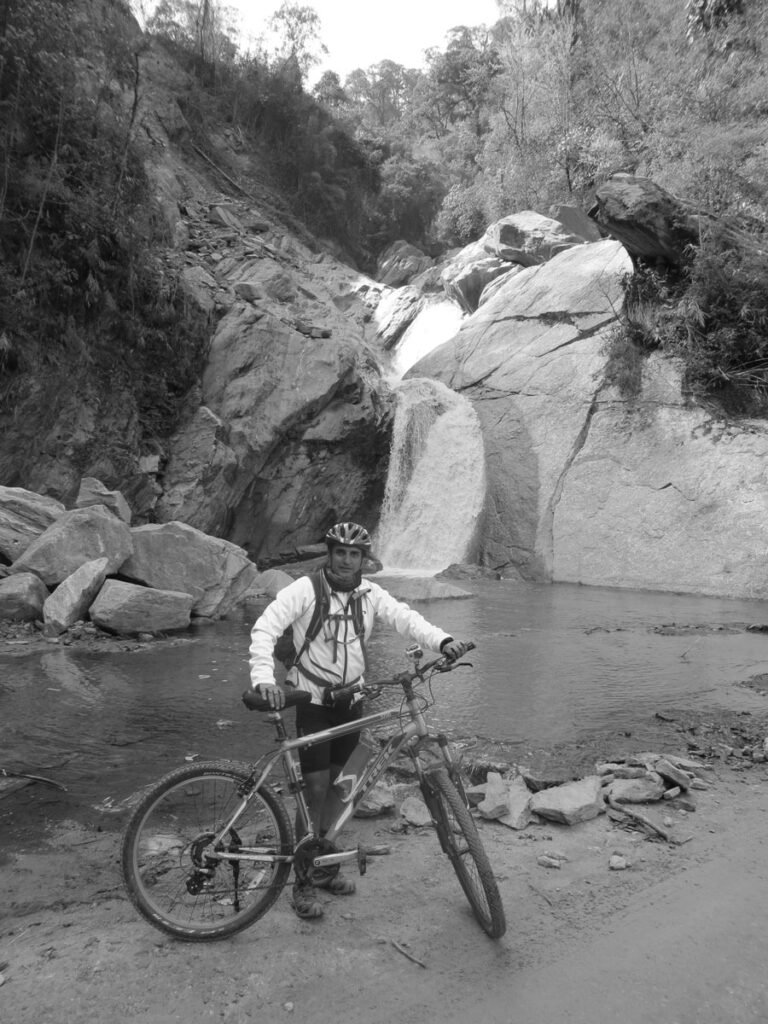

To be on the saddle again in the Himalaya is always a joyous feeling and an unexplainable expression of freedom. The thrilling part of any ride in the mountains is the descent, and the more dangerous and technical it is, the more exciting and satisfying. The route to the main highway on the dusty trail down the mountainside was no exception as we twisted, turned and rattled down a rocky, dusty road at a breakneck speed. At some point, I felt I would dislocate my joints!

Tenzing and Jigmi were much more skilled and I was generally on my own after the first half an hour. Their competence and experience of living and cycling in the mountains enabled them to move much quicker and negotiate the treacherous trails deftly whereas I would slow down to take that risky hairpin. But this also took the pressure off me to set the pace and I was able to observe and embrace the beauty around me. The desire to explore and immerse myself in the wilderness was the main motivation behind cycling in the wild other than the pleasure of the sheer grit and struggle of climbing a hefty mountain. On our left was the mountainside, thickly forested with poplar, oak and conifer trees interspersed with rhododendron shrubs, the unmistakably bright pink and red flowers brightening the dense green forests. Sikkim has more than 40 varieties of rhododendron and it is also the state tree.

I pedalled along the trails passing hamlets with row after row of white Buddhist prayer flags, their presence calming the energies in the air. All I could hear was the crunch of dry pine needles on the trail under the swirling tyres, the soft sound of my chain turning, the wind on my face and the odd splash of muddy water as I rode into a puddle, the muddy water imprinting itself on my glasses and jersey.

Mangan is at an altitude of 956 m/3,136 ft and is the capital of the North Sikkim district, and so we

descended almost 1,000 m/3,280 ft on the first day, knowing very well, that the following day and the days after that would be sheer climbs. On the way down to Mangan, Tenzing had a bad fall and injured his knee and shin quite badly. Fortunately for us, just a little ahead was an army medical camp and he was stitched up and continued to ride on regardless of the injury or the pain that he must have been experiencing. As I cycled on through the heat of the day, I pondered over his positive attitude; the guts and the grit that he displayed strengthened my own beliefs of their importance in all spheres of our lives. Tenzing could have easily chosen to abandon the ride to Mangan and ride in the vehicle for the remainder of the day, but he chose to complete the mission.

The road to Chungthang from Mangan was a steady climb and though we left early in the morning the sun blazed strongly making the task of climbing more arduous. The road was not asphalt but packed mud and crushed small rocks, ideal for mountain biking, but also torturous for climbing when not having trained on the surface. It was a steady climb with an elevation gain of 1,285 m/4,200 ft over 30 km to Chungthang, our midday halt. It was hot in some parts but shady in a few sections depending on which side of the mountain we were riding on. The North Sikkim road is in a deep valley surrounded by towering mountains and the Lachung river meandered past many villages, thinly populated and comprised of mainly wood and stone homes. There were some concrete structures as well, with many buildings coming up in some of the villages.

I left Chungthang in good spirits and initially my energy was good. However, it began to drizzle and then rain, and once I had donned the rain gear, my speed dropped substantially. The rain was not heavy enough for me to have worn my rain pants, but having just recovered from the fever, I could feel the chilly rain numb my legs. It was at this point that I began to feel the fatigue set in. The illness of the last week was now beginning to slow me down even as I gained altitude again, my pace dropping significantly and dropping behind the other riders. This time spent on my own, in the backdrop of the diminishing sunlight, brought up many of my buried thoughts and anxieties. As I worked through them, I began to realize, as I had on previous adventures, that much of what keeps our bravest thoughts caged is the thought that we are powerless. Our fear gives our false beliefs the burst of power to overwhelm us.

The climb to Lachen continued to intensify. It was dusk now and some of the old dried-up trees by the roadside, with gnarled branches, looked straight out of a Lord of the Rings movie. Perhaps it was the fatigue or my incoherent mind that began to imagine they would start to walk towards me any moment, and pluck me and the bicycle from the road and toss us into the air. I chuckled to myself at the madness of my mind!

I could feel the tiredness overcome my will to go on, and the temptation to take a ride to Lachen over the last 9 km grow, but I held back that thought and continued to pedal even as the air turned colder and

the temperature dropped to about 5 degrees Celsius. Rhododendron shrubs now covered the landscape even as the river gorge to my left got deeper.

Dusk gave way to darkness and I continued to pedal towards our halt for the night at Lachen. My thoughts moved to envision the climb to Thangu the following day and then to Lake Gurudongmar. The practice was to awaken very early and leave from Thangu so as to reach the lake before noon and leave within an hour, as post that the ferocity of the winds raging across the high- altitude plateau was usually severe and dangerous for cyclists and motorbikers. In the distance I saw a vehicle come towards me, its headlights blinding me. I realized it was Palden who had got worried and turned back to pick me up. I told him, ‘Palden, I can do it. It is just a few more kilometres.’ It was past 6 p.m. now and quite cold in the early springtime of Sikkim. I reached the lodgings where we were to stay the night, and I was quite happy to have completed the distance through challenging terrain and gradient. While the roads built by the BRO in Ladakh had gradients of 3–4%, North Sikkim road gradients in most sections were easily in the range of 4–10% and had many switchbacks that kept me on the road for close to nine hours over just 56 km.

Just a few minutes later, as I sat down for a meal of soup and rice in the warm kitchen of the lodging, Palden’s wife called from Gangtok. My father had had a heart attack and was to be operated on the following day in Delhi. The news was unexpected and worrying but I instantly knew that I would have to abandon the climb to Thangu and Lake Gurudongmar and head back to Delhi. The weather outside continued to deteriorate. The following morning, Palden and his friends helped to dismantle the bicycle and put it back in the box and arranged for a vehicle to take me back to Bagdogra airport. As they all said goodbye to me, Palden placed a Tibetan white khata scarf around me—a blessing for a safe journey. I was touched by his gesture and promised to return someday